January has a way of sobering everyone up. The decorations come down, inboxes refill, and that ambitious end-of-year deal suddenly becomes very real. The contracts are signed, the announcements are out, and now someone has to make the merger actually work. This is where the first 100 days quietly decide whether the deal settles in nicely or becomes the thing everyone politely avoids talking about by March.

Post-merger integration is often framed as a people and process exercise, but technology is the backbone holding the whole plan upright. You can have alignment workshops, leadership town halls, and beautifully worded vision statements, but if the systems do not cooperate, the 100-day plan turns into a list of postponed intentions. January optimism does not survive incompatible ERPs.

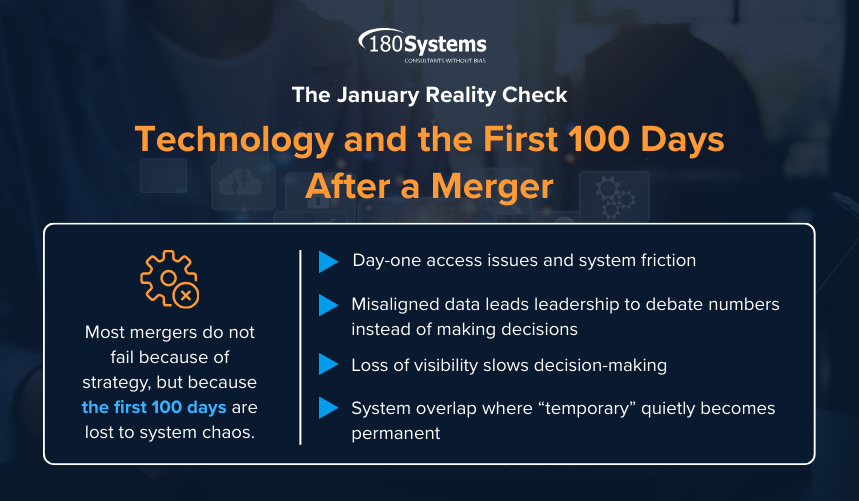

The first challenge usually appears in the form of access. Day one arrives and suddenly half the team cannot log in, the other half has access to things they probably should not, and someone is still waiting for credentials that were “approved last week.” This is not dramatic, but it is disruptive. Momentum matters early on, and nothing kills momentum faster than basic system friction. The 100-day plan assumes people can work. Technology decides whether that assumption holds.

Data alignment follows closely behind. Both organisations bring their own definitions, structures, and reporting logic into the new year. Revenue means one thing here and something slightly different there. Customer records look similar but refuse to match. January becomes a month of reconciliation rather than execution. Without early data alignment, leadership spends the first quarter debating numbers instead of acting on them.

Then there is the question of visibility. The 100-day plan typically promises clarity, stability, and progress. Technology either enables that or quietly obscures it. If reporting is delayed, fragmented, or stitched together manually, leaders lose confidence in what they are seeing. Decisions slow down. Meetings multiply. The plan still exists, but it starts drifting away from reality.

System overlap also makes an appearance once the holiday glow fades. Two CRMs, multiple finance tools, duplicate integrations, and parallel workflows all seem manageable at first. After all, it is only temporary. Except temporary has a habit of becoming permanent by Q2. Every extra system adds cost, confusion, and operational drag. The 100-day plan works best when it includes clear decisions about what stays, what goes, and what gets addressed later, intentionally, not accidentally.

Change fatigue is another January guest that overstays its welcome. Employees are already easing back into work, resetting priorities, and catching up on what they missed. Layering unclear technology changes on top of that creates frustration. When systems shift without explanation or training, productivity dips and patience runs thin. Technology choices need context, communication, and timing. Otherwise, even the best decisions feel disruptive.

When technology is considered early and realistically, the first 100 days feel very different. Access is planned. Data priorities are defined. Reporting is trusted. Leaders can see progress without asking for three versions of the same number. The organisation spends January building rather than untangling.

A strong technology lens does not overcomplicate the 100-day plan. It simplifies it. It forces clear decisions, sets boundaries, and creates a foundation that supports the human side of integration instead of fighting it. The goal is not perfection in the first 100 days. The goal is stability, visibility, and forward motion.

January is always a reset. For post-merger teams, it is also a proving ground. The excitement of the deal has passed, and now the work begins. When technology is aligned with the 100-day plan, the merger stops feeling like a resolution that fades by mid-month and starts feeling like something built to last.

PHJLJL looks suspiciously shady. I’d be very careful before putting any money in there. Just a heads up. Do your research before hitting phjljl.

Hey, just checked out uujlactivity! Looks like a promising spot for some fun. Gonna give it a try and see what the hype is about. Check it out for yourself at uujlactivity!

Yo, looking for some serious gaming action? Heard vip games on vipgamecasino.net are where it’s at. Gonna dive in and see if I can hit that jackpot! You can find it here: vip games